Industrial Revolution and James Lowe

When you think of the Industrial Revolution what images do you conjure up? For me its the hardship and bleakness of smoke infested towns, enormous brick buildings pumping, whirring, grinding and shunting – coal, tin, wool, cotton, iron and steam. But its not only the bleakness of the places, it’s also the bleakness of the people – lined, weary faces of those trying to many a penny to survive, fresh faced excitement of those arriving from the countryside, and aristocratic men, in crisp, starched shirts and waistcoats inventing and creating new and even more fabulous inventions.

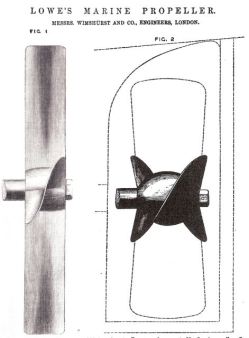

James Lowe was one such inventor. Lowe had worked as a mechanist and smoke jack maker and invented a screw propeller for ships. On the 23 March 1838 he took out a patent for a new screw propeller which ensured his place in history. New inventions were taken to the Royal Navy weekly, and at this time there was very little money to be made from such things. But Lowe would not give up and he spent all his wife’s money on his experiments and a succession of patents reducing the family to complete poverty by the early 1850’s. Therefore it might seem strange, that his daughter, Henrietta Vansittart (nee Lowe) excelled herself to become a respected engineer and inventor in her own right, at a time when Victorian women should have been doing anything but science.

Henrietta Vanisittart nee Lowe

Henrietta was born in 1833, to James and Marie Lowe (nee Barnes) – she did not have the most fortunate of circumstances, she was the third daughter of six sister and two bothers, and her father had almost bankrupted the family by 1852 through his desire to invent. However, Henrietta it seems was a social climber and had dreams of grandeur, and by 1855 she had married a lieutenant in the 14th Dragoons, Frederick Vansittart who had been based in Paris. Soon after they bought a house in Clarges Street, London and it seems he sold his commission to they could set up home. But, this was not good enough for Henrietta and in 1859 she started an affair, which lasted 12 years with the novelist and politician, Edward Bulwer Lytton. Lytton was a man of social status and Henrietta clearly had an effect on him, although perhaps not to Disrealis liking and is said to have blamed Lyttons absences from the House of Commons on his association with Henrietta. Lytton became ill and in 1873 died, leaving Henrietta £1200 in his will and very oddly her husband, £300. She returned to her husband and lived in Twickenham. Henrietta was clearly a highly charismatic and feisty young lady who knew what she wanted and did not allow things to stand in her way. (Image 1 – see source

Henrietta was born in 1833, to James and Marie Lowe (nee Barnes) – she did not have the most fortunate of circumstances, she was the third daughter of six sister and two bothers, and her father had almost bankrupted the family by 1852 through his desire to invent. However, Henrietta it seems was a social climber and had dreams of grandeur, and by 1855 she had married a lieutenant in the 14th Dragoons, Frederick Vansittart who had been based in Paris. Soon after they bought a house in Clarges Street, London and it seems he sold his commission to they could set up home. But, this was not good enough for Henrietta and in 1859 she started an affair, which lasted 12 years with the novelist and politician, Edward Bulwer Lytton. Lytton was a man of social status and Henrietta clearly had an effect on him, although perhaps not to Disrealis liking and is said to have blamed Lyttons absences from the House of Commons on his association with Henrietta. Lytton became ill and in 1873 died, leaving Henrietta £1200 in his will and very oddly her husband, £300. She returned to her husband and lived in Twickenham. Henrietta was clearly a highly charismatic and feisty young lady who knew what she wanted and did not allow things to stand in her way. (Image 1 – see source

During this time, Henrietta took a keen interest in her fathers work and accompanied him on the HMS Bullfinch in 1857 to test out the new screw propeller. She had her own ideas for how it could be developed, and after her father was tragically killed by a cart crossing the road in London in 1866, she took on her fathers work without any formal scientific or engineering training. Within 2 years she had patented another propeller to allow ships to move faster and smoother and use less fuel. In 1868, the Vansittart Propeller was patented and was used on HMS Druid – she won numerous awards for this, had articles written on her in the Times Newspaper and attended exhibitions all over the world. She was clearly a remarkable woman. It is believed that she was the only lady who ever wrote, read and illustrated with her own drawings and diagrams a scientific paper before members of the Scientific Institution.

Henrietta and Twickenham

Of course, no street or person would be complete without some intrigue, mystery and scandal and Henrietta certainly had some interesting moments. It is one of my favourite things about researching a house history – the stories of the people who lived there. The little scraps that give us a glimpse into the past – of squabbles and stand offs, intrigue and intellect, parties and politicians. Montpelier Row has certainly had its fair show of arguments,

Henrietta seems to have lived a colourful life in all areas. It is perhaps strange that she left her husband to have her affair with Lytton in this age, and that Lytton then left both Henrietta and Frederick money in his will, £1200 to her and £300 to him, no small sum in 1873. Stranger still perhaps that she then went back to her husband. Happily or not, who knows.

Mr & Mrs vansittart appear to have become property owners owning a number of houses in Montpelier Row Twickenham as well as on Maids of Honor by Richmond Green. These were and still are desirable and expensive addresses.

Maids of Honor Row – Richmond Green.

. The 1871 census lists them at 4 Maids of Honor Row although records suggest she was there in 1869 without her husband. Perhaps she had bought it with funds from her patent, inheritence or from Lytton. Henry George Bohn in a letter to the Richmond Twickenham Times in 1879 states that she arrived in Twickenham around 1874. In a later letter by Bohn he talks about 4 houses that she had purchased in complete squalor for between £200-£300, and which had then been converted into two, these appear to have been Number 4 and 5 which later became Seymour House and 1 and 2, which were known as Bell House and St Maur’s Priory. It seems by 1880 she had No 1, St Maur’s Priory (Which had been named by her) and 2, Bell House left in her possession as she had sold the others off. The 1881 census, shows that Frederick and Henrietta were living at No 1 Montpelier Row whose main frontage was on the Richmond Road.

The 1881 census shows that Frederick and Henrietta were now living at No 1 Montpelier Row, known at this time as St Mary’s Priory, or St Maurs Priory which had been named by Henrietta.

1 Montpelier Row, Twickenham (Originally Numbers 1 and 2)

In 1878, Bell House, Number 2 was offered for lease for the sum of £100 and Seymour House, Number 3 was also offered for sale for £73,10s. Both properties were owned by Henrietta at this time and were offered for sale by Mr Fowler on 25 June 1878. It appears that a neighbour, Henry George Bohn, the infamous fine art dealer, publisher and book collector, with whom there seems to have been some rivalry and dispute purchased Seymour House from Henrietta in 1879, paying £1100.00 – a vast increase on the alleged two hundred pounds she had spent only a few years earlier.

Henry George Bohn was the Vansittarts neighbour, living at North End House, just the other side of the Richmond Road. There appears to have been a great deal of rivalry amongst the two households, not least perhaps because of Henrietta’s desire to own and lease property – the same property that Bohn also wanted to own and lease. There was some argument with the local council in 1879, as the row had been changed to Montpelier Row to which Bohn took great displeasure and wrote to the Richmond Twickenham Times.(5) He had erected a sign on the from of the wrought iron railings of No 1, Henrietta’s house which stated Montpelier Row, He claims this had been agreed with Henrietta and that they had been on speaking on terms about it. However, to his annoyance, early one morning he had spied from his house, Mr Vansittart at the top of a ladder, painting the sign out! I can quite imagine the surprise and intrigue of curtains twitching as the early morning sun rose in Twickenham, to reveal an ageing Mr Vanisttart balanced among the top of a ladder, with an incensed wife in her long skirts, swishing in the dust at the bottom issuing her instructions.

Bohn took to paper soon after, seemingly to air his grievances about Henrietta in public – entitle ‘The Montpelier Row Difficulty’, he writes that:

‘It is with great regret that I find myself brought once more into a verbal conflict with Mrs Vansittart, but she is inexorable, and by way of publicly introducing, what appear to me to be mere figment of the brain, contrives to make me the scapegoat. I have no choice, therefore, but to reply to her, and bring out what may well be called the facts of a Tweedledum affair’ (6)

It seems that Henrietta had claimed that she had spent thousands of pounds on improving the row, both the buildings she had purchased but also the area of land opposite, which Bohn claims that he had in fact sectioned off and made good to stop costermongers and other nuisances taking over himself. She stresses that she has done so much more for the neighbourhood than Bohn has ever done – keeping up with the Jones of the Victorian age.

He also airs in public his annoyance at her private affairs about the purchase and sale of her properties, and mortgages she had taken out. Indeed, what obviously had been private discussions seems to have reached a head in 1879/1880 as both wrote backwards and forwards to the paper airing their grievances of one another’s behaviour over several years. A very public affair!

Sadly Henrietta met a very unhappy end. In the autumn if 1883, it seems she was attending the North East Coat Exhibition of Naval Architecture and Marine Engineer at Tynemouth. She was, found wandering the streets in a very confused state of mind and was consequently committed to the Tyne City Lunatic Asylum, where she died early in 1883 on anthrax and mania. A sad end to an eventful life. One wonders why she was not moved back down South, had she fallen out with her husband again? Had she of lived one wonders what she would have gone on to achieve as a great woman engineer.

SOURCES

1.Epsom and Ewell History Explorer, James Lowe and his daughter Mrs Henrietta Vansittart, http://www.epsomandewellhistoryexplorer.org.uk/Lowe.html, first accessed 15/2/2017

2.Howes, A, Capitalism’s Cradle – An Economic History Blog, http://antonhowes.tumblr.com/post/115859870959/female-inventors-of-the-industrial-revolution-part

3.Intriguing History, Henrietta Vansittart Enginner, http://www.intriguing-history.com/henrietta-vansittart-engineer/, first accessed 10/2/2017

4.Wikipedia, James Lowe, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Lowe_(inventor), first accessed 10/2/2017

5. Richmond Local Studies Library, Richmond Twickenham Times, extract from a letter written to the paper from Henry George Bohn, dated 1 July 1879.

6. Richmond Local Studies Library, Richmond Twickenham Times, extract from a letter written to the paper from Henry George Bohn, entitled The Montpelier Row Difficulty.

7. Photographs are all taken from my own personal archive and are copyright to Emma Louise Tinniswood